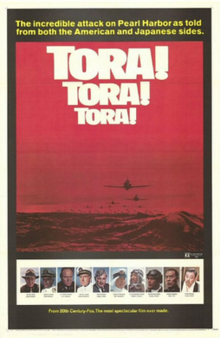

Tora! Tora! Tora!

| Tora! Tora! Tora! | |

|---|---|

Original movie poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Fleischer Japanese sequences: Toshio Masuda Kinji Fukasaku |

| Produced by | Elmo Williams Richard Fleischer |

| Screenplay by | Larry Forrester Hideo Oguni Ryuzo Kikushima Uncredited: Akira Kurosawa |

| Based on | Tora! Tora! Tora! by Gordon W. Prange and The Broken Seal by Ladislas Farago |

| Starring | Martin Balsam Joseph Cotten Sō Yamamura Tatsuya Mihashi E. G. Marshall James Whitmore Jason Robards |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

| Cinematography | Charles F. Wheeler Shinsaku Himeda Masamichi Satoh Osamu Furuya |

| Editing by | Pembroke J. Herring Chikaya Inoue James E. Newcom |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

| Release date(s) |

|

| Running time | 144 minutes |

| Country | United States Japan |

| Language | English/Japanese |

| Budget | $25,485,000[1][2] |

| Box office | $29,548,291 (domestic)[3] |

Tora! Tora! Tora! (Japanese: トラ・トラ・トラ) is a 1970 American-Japanese war film that dramatizes the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The film was directed by Richard Fleischer and stars an ensemble cast, including Martin Balsam, Joseph Cotten, Sō Yamamura, E.G. Marshall, James Whitmore and Jason Robards. The film uses Isoroku Yamamoto's famous quote, saying the attacks would only serve to "... awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve", although it may have been apocryphal.

The title is the Japanese code-word used to indicate that complete surprise had been achieved. Tora (虎, pronounced [tòɽá])) literally means "tiger", but in this case was an acronym for totsugeki raigeki (突撃雷撃, "lightning attack").

Contents[show] |

Plot [edit]

|

|

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (December 2011) |

A change-of-command ceremony aboard the Japanese battleship Nagato, flagship for the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (Sō Yamamura) takes place in 1941. He takes command from Zengo Yoshida (Junya Usami). The two discuss America's embargo that starves Japan of raw materials. While both agree that a war with the United States would be a complete disaster, army hotheads and politicians push through an alliance with Germany and start planning for war. With the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, regarded as a "knife to the throat of Japan", Yamamoto orders the planning of a preemptive strike, believing Japan's only hope is to annihilate the American Pacific fleet at the outset of hostilities.

When planning the attack, the Japanese commanders debate Pearl Harbor's exposure to a torpedo attack, but realize that torpedoes dropped from an aircraft will fall and submerge at least 75 feet (23 m) below the surface. Since Pearl Harbor is only 40 feet (12 m) deep, the Americans feel they have a natural defense against torpedoes but the Japanese modify their torpedoes.

In a major intelligence victory, American intelligence in Washington manages to break the Japanese Purple Code, allowing the United States to intercept radio transmissions the Japanese think are secret. American intelligence in general appears lax, although Pearl Harbor does increase air patrols and goes on full alert well before the raid.

Japanese commanders call on the famous Air Staff Officer Minoru Genda (Tatsuya Mihashi) to mastermind the attack. Genda's Japanese Naval Academy classmate, Mitsuo Fuchida (Takahiro Tamura), is chosen to be the leader of the attack. [4]At Pearl Harbor, although hampered by a late-arriving critical intelligence report about the attack fleet, Admiral Kimmel (Martin Balsam) and General Short (Jason Robards) do their best to enhance defenses. Short orders his aircraft to be concentrated in the middle of their airfields to prevent sabotage; leading to a pointed bit of talk between two officers when one objects to the order by saying, "Suppose there's an air raid?"

Diplomatic tensions increase between the U.S. and Japan as the Japanese ambassador to the United States asks Tokyo for more information to aid in negotiations to avoid war. Army General Tojo (Asao Uchida) is adamantly opposed to any last minute attempts at peace. The Japanese commence a series of 14 radio messages from Tokyo to the Japanese embassy in Washington that will conclude with the declaration of war. The Americans are translating the radio messages faster than the Japanese embassy. Hence, the Americans know of the attack before the Japanese ambassador informs them.

On the morning of December 7, decision makers in Washington and Hawaii are seen enjoying a leisurely routine while American intelligence works feverishly to interpret the coded transmissions and learns the final message will be received precisely at 1:00 pm Washington time. American intelligence notes that the final message instructs the Japanese Ambassador to destroy their code machines after they decode the last of the 14 messages, an ominous point. Attempts to convey this message to American commanders fail because they are enjoying a Sunday of playing golf and horseback riding. Finally, Chief of Naval Operations Harold R. Stark (Edward Andrews) is informed of the increased threat, but decides not to inform Hawaii until after calling the President, although it is not clear if he takes any action at all.

Finally, at 11:30 am Washington time, Colonel Bratton (E.G. Marshall) convinces the Army Chief of Staff, General George Marshall (Keith Andes), that a greater threat exists, and Marshall orders that Pearl Harbor (and all other Pacific installations) be notified of an impending attack. An American destroyer, USS Ward (DD-139), spots a Japanese midget submarine trying to slip through the defensive net and enter Pearl Harbor, sinks it, and notifies the base. Although the receiving officer, Lieutenant Kaminsky (Neville Brand), takes the report of an attempted enemy incursion seriously, Captain John Earle (Richard Anderson) at Pearl Harbor demands confirmation before calling an alert. Admiral Kimmel later learns of this negligence and is furious he was not told of this enemy action immediately. Just after 7:00 am, the two privates posted at the remote radar, Joseph Lockard and George Elliot, spot the incoming Japanese aircraft and inform the Hickham Field Information Center, but the Army Air Forces Lieutenant in charge, Kermit Tyler, dismisses the report, thinking it is a group of American B-17 bombers coming from the mainland, and he is frankly too tired to care.

The Japanese intend to break off negotiations (they did not intend to issue a formal declaration of war) at 1 pm Washington time, 30 minutes before the attack. However, the typist for the Japanese ambassador is slow, and cannot decode the 14th part fast enough. A final attempt to warn Pearl Harbor is stymied by poor atmospherics and bungling when the telegram is not marked urgent; it will be received by Pearl Harbor after the attack. The incoming Japanese fighter pilots are pleasantly surprised when there isn't even any anti-aircraft fire as they approach the base. As a result, the squadron leader radios in the code phrase marking that complete surprise for the attack has been achieved: "Tora, Tora, Tora!"

Once the attack is launched, the Americans are not even aware that they are under an organized attack until the first bomb detonates, and their resulting hasty response is desperate and only partially effective. The aircraft security precautions prove a disastrous mistake that allows the Japanese aerial forces to destroy the U.S. aircraft on the ground with ease, thereby crippling an effective aerial counter-attack: all the aircraft on the runways at the major airfields were destroyed spectacularly either as they took off or while they were still parked. Two American fighter pilots (portrayals of Second Lieutenants Ken Taylor and George Welch) race to remote Haleiwa and manage to take off to engage the enemy, as the Japanese have not hit the smaller airfields.

The catastrophic damage to the naval base is widespread, with sailors fighting as long as they can and then abandoning sinking ships and jumping into the water with burning oil on the surface. At the end of the attacks, with the Pearl Harbor base in flames, its frustrated commanders finally get the Pentagon's telegram warning them of impending danger. The US Secretary Of State, Cordell Hull (George Macready), is stunned at learning of this brazen attack and urgently requests confirmation of it before receiving the Japanese ambassador, who is waiting just outside his office. In Washington, the distraught Japanese ambassador (Shōgo Shimada), helpless to explain the late ultimatum and the unprovoked sneak attack, is bluntly rebuffed by Hull, who coldly replies to the final Japanese communique: "In all my fifty years of public service, I have never seen a document that was more crowded with infamous falsehoods and distortions – on a scale so huge that I never imagined until today that any government on this planet was capable of uttering them!"

The Japanese fleet commander, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo (Eijiro Tono), refuses to launch the third wave of carrier aircraft out of fear of exposing his six carriers to increased risk of detection and destruction from the still-absent US carriers. At his home base, Admiral Yamamoto laments the fact that the Americans did not receive the declaration of war until after the attack had started, noting that nothing would infuriate the Americans more. He is quoted as saying: "I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve."[N 1]

Cast [edit]

The film was deliberately cast with actors who were not true box-office stars, in order to place the emphasis on the story rather than the actors who were in it. The original cast list had included many Japanese amateurs.[6] Cast in credits order:[7]

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Martin Balsam | Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet |

| So Yamamura | Kaigun Taishō (Admiral) Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief, Combined Fleet |

| Joseph Cotten | Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson |

| Tatsuya Mihashi | Kaigun Chūsa (Commander) Minoru Genda, Air Staff, 1st Air Fleet |

| E. G. Marshall | Colonel Rufus S. Bratton, Chief, Far Eastern Section, Military Intelligence Division, War Department |

| James Whitmore | Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Commander, Aircraft Battle Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet |

| Takahiro Tamura | Kaigun Chūsa (Commander) Mitsuo Fuchida, Commander, Air Group, Akagi |

| Eijiro Tono | Kaigun Chūjō (Vice Admiral) Chuichi Nagumo, Commander-in-Chief, 1st Air Fleet |

| Jason Robards | Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Army Forces Hawaii |

| Wesley Addy | Lieutenant Commander Alwin D. Kramer, Cryptographer, OP-20-G |

| Shogo Shimada | Kaigun Taishō (Admiral) Kichisaburo Nomura, Japanese Ambassador to the United States |

| Frank Aletter | Lieutenant Commander Francis J. Thomas, Command Duty Officer, USS Nevada |

| Koreya Senda | Prime Minister Prince Fumimaro Konoe |

| Leon Ames | Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox |

| Junya Usami | Kaigun Taishō (Admiral) Zengo Yoshida, Minister of the Navy |

| Richard Anderson | Captain John B. Earle, Chief of Staff, 14th Naval District |

| Kazuo Kitamura | Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka |

| Keith Andes | General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army |

| Susumu Fujita | Kaigun Shōshō (Rear Admiral) Tamon Yamaguchi, Commander, Second Carrier Division |

| Edward Andrews | Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations |

| Bontaro Miyake | Kaigun Taishō (Admiral) Koshiro Oikawa, Minister of the Navy |

| Neville Brand | Lieutenant Harold Kaminski, Duty Officer, 14th Naval District |

| Ichiro Ryuzaki | Kaigun Shōshō (Rear Admiral) Ryunosuke Kusaka, Chief of Staff, 1st Air Fleet (as Ichiro Reuzaki) |

| Leora Dana | Mrs. Kramer |

| Asao Uchida | Rikugun Taishō (General) Hideki Tojo, Minister of War |

| George Macready | Secretary of State Cordell Hull |

| Norman Alden | Major Truman H. Landon, Commanding Officer, 38th Reconnaissance Squadron |

| Kazuko Ichikawa | Geisha in Kagoshima |

| Walter Brooke | Captain Theodore S. Wilkinson, Director of Naval Intelligence |

| Hank Jones | Davey, civilian student pilot |

| Rick Cooper | Second Lieutenant George Welch, pilot, 47th Pursuit Squadron |

| Karl Lukas | Captain Harold C. Train, Chief of Staff, Battle Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet |

| June Dayton | Miss Ray Cave, secretary, OP-20-G |

| Ron Masak | Lieutenant Lawrence E. Ruff, Communications Officer, USS Nevada |

| Jeff Donnell | Miss Cornelia Clark Fort, civilian flying instructor |

| Shunichi Nakamura | Kaigun Daisa (Captain) Kameto "Gandhi" Kurishima, Senior Staff Officer, Combined Fleet |

| Richard Erdman | Colonel Edward F. French, Chief, War Department Signal Center |

| Hiroshi Nihonyanagi | Kaigun Shōshō (Rear Admiral) Chuichi Hara, Commander, 5th Carrier Division (as Kan Nihonyanagi) |

| Jerry Fogel | Lieutenant Commander William W. Outerbridge, Commanding Officer, USS Ward |

| Carl Reindel | Second Lieutenant Kenneth M. Taylor, pilot, 47th Pursuit Squadron |

| Elven Havard | Mess Attendant 3rd Class Doris Miller, USS West Virginia |

| Edmon Ryan | Rear Admiral Patrick N. L. Bellinger, Commander, Patrol Wing Two |

| Toshio Hosokawa | Kaigun Shōsa (Lieutenant Commander) Shigeharu Murata, Commander, 1st Torpedo Attack Unit, Akagi (as Tosio Hosokawa) |

| Hisao Toake | Saburo Kurusu, Japanese Special Envoy to the United States |

| Toru Abe | Kaigun Shōshō (Rear Admiral) Takijiro Inishi, Chief of Staff, 11th Air Fleet (uncredited) |

| Hiroshi Akutagawa | Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Marquis Koichi Kido (uncredited) |

| Kiyoshi Atsumi | Japanese Cook #1 (uncredited) |

| Harold Conway | Counselor Eugene Dooman, U.S. Embassy in Tokyo (uncredited) |

| Dick Cook | Lieutenant Commander Logan C. Ramsey, Chief of Staff, Patrol Wing Two (uncredited) |

| Jerry Cox | First Lieutenant Kermit A. Tyler, Executive Officer, 78th Pursuit Squadron and Officer in Charge, Pearl Harbor Intercept Center (uncredited) |

| Mike Daneen | First Secretary Edward S. Crocker, U.S. Embassy in Tokyo (uncredited) |

| Francis De Sales | Lieutenant Commander Arthur H. McCollum, Head, Far East Asia Section, Office of Naval Intelligence (uncredited) |

| Dave Donnelly | Major Gordon A. Blake, Operations Officer, Hickam Field (uncredited) |

| Bill Edwards | Colonel Kendall J. Fielder, G-2 Intelligence Officer, U.S. Army Forces Hawaii (uncredited) |

| Dick Fair | Lieutenant Colonel Carroll A. Powell, Chief Signal Officer, U.S. Army Forces Hawaii (uncredited) |

| Charles Gilbert | Lieutenant Colonel William H. Murphy, Air Warning Development Officer, U.S. Army Forces Hawaii (uncredited) |

| Hisashi Igawa | Kaigun Daii (Lieutenant) Mitsuo Matsuzaki, pilot, 1st Torpedo Attack Unit, Akagi (uncredited) |

| Robert Karnes | Major John H. Dillon, Knox's aide (uncredited) |

| Randall Duk Kim | Tadao, Japanese messenger boy (uncredited) |

| Berry Kroeger | General (uncredited) |

| Akira Kume | First Secretary Katsuzo Okumura, Japanese Embassy in Washington, D.C. (uncredited) |

| Dan Leegant | George Street, RCA Honolulu District Manager (uncredited) |

| Ken Lynch | Rear Admiral John H. Newton, Commander, Cruisers, Scouting Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander, Task Force 12 (uncredited) |

| Mitch Mitchell | Colonel Walter C. Phillips, Chief of Staff, U.S. Army Forces Hawaii (uncredited) |

| Walter Reed | Vice Admiral William S. Pye, Commander, Battle Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (uncredited) |

| Robert Shayne | Commander William H. Buracker, Operations Officer, Aircraft Battle Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (uncredited) |

| Edward Sheehan | Brigadier General Howard C. Davidson, Commander, 14th Pursuit Wing (uncredited) |

| Tommy Splittgerber | Ed Klein, RCA telegraph operator (uncredited) |

| G. D. Spradlin | Commander Maurice E. Curts, Communications Officer, U.S. Pacific Fleet (uncredited) |

| Larry Thor | Major General Frederick L. Martin, Commander, Hawaiian Air Force (uncredited) |

| George Tobias | Captain on Flight Line at Hickam Field (uncredited) |

| Harlan Warde | Brigadier General Leonard T. Gerow, Chief, War Plans Division, War Department (uncredited) |

| Meredith Weatherby | Joseph C. Grew, U.S. Ambassador to Japan (uncredited) |

| David Westberg | Ensign Edgar M. Fair, USS California (uncredited) |

| Bruce Wilson | Private Joseph L. Lockard, radar operator, Opana Point (uncredited) |

| Bill Zuckert | Admiral James O. Richardson, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet (uncredited) |

Production [edit]

Veteran 20th Century Fox executive Darryl F. Zanuck, who had earlier produced The Longest Day (1962), wanted to create an epic that depicted what "really happened on December 7, 1941", with a "revisionist's approach". He believed that the commanders in Hawaii, General Short and Admiral Kimmel, though scapegoated for decades, provided adequate defensive measures for the apparent threats, including relocation of the fighter aircraft at Pearl Harbor to the middle of the base, in response to fears of sabotage from local Japanese. Despite a breakthrough in intelligence, they had received limited warning of the increasing risk of aerial attack.[1] Recognizing that a balanced and objective recounting was necessary, Zanuck developed an American-Japanese co-production, allowing for "a point of view from both nations."[9] He was helped out by his son, Richard D. Zanuck, who was chief executive at Fox during this time.

Production on Tora! Tora! Tora! took three years to plan and prepare for the eight months of principal photography.[9] The film was created in two separate productions, one based in the United States, directed by Richard Fleischer, and one based in Japan.[10] The Japanese side was initially to be directed by Akira Kurosawa, who worked on script development and pre-production for two years. But after two weeks of shooting, he was replaced by Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku, who directed the Japanese sections.[11][10]

Richard Fleischer said of renowned director Akira Kurosawa's role in the project:

Well, I always thought that even though Kurosawa was a genius at film making and indeed he was, I sincerely believe that he was miscast for this film, this was not his type of film to make, he never made anything like it and it just wasn't his style. I felt he was not only uncomfortable directing this kind of movie but also he wasn't used to having somebody tell him how he should make his film. He always had complete autonomy, and nobody would dare make a suggestion to Kurosawa about the budget, or shooting schedule, or anything like that. And then here he was, with Darryl Zanuck on his deck and Richard Zanuck on him and Elmo Williams and the production managers, and it was all stuff that he never had run into before, because he was always untouchable. I think he was getting more and more nervous and more insecure about how he was going to work on this film. And of course, the press got a hold of a lot of this unrest on the set and they made a lot out of that in Japan, and it was more pressure on him, and he wasn't used to that kind of pressure.[12]

Larry Forrester and frequent Kurosawa collaborators Hideo Oguni and Ryuzo Kikushima wrote the screenplay, based on books written by Ladislas Farago and Gordon Prange of the University of Maryland, who served as a technical consultant. Numerous technical advisors on both sides, some of whom had participated in the battle and/or planning, were crucial in maintaining the accuracy of the film. Minoru Genda, the man who largely planned and led the attack on Pearl Harbor was an uncredited technical advisor for the film.[1]

Four cinematographers were involved in the main photography: Charles F. Wheeler, Sinsaku Himeda, Masamichi Satoh and Osami Furuya.[13] They were jointly nominated for the Academy Award for Best Cinematography. A number of well-known cameramen also worked on the second units without credit, including Thomas Del Ruth and Rexford Metz.[13] The second unit doing miniature photography was directed by Ray Kellogg, while the second unit doing plane sequences was directed by Robert Enrietto.

Noted composer Jerry Goldsmith composed the film score and Robert McCall painted several scenes for various posters of the film.[14]

The flying scenes were complex to shoot, and can be compared to the 1969 film Battle of Britain. The 2001 film Pearl Harbor would contain cut scenes from both films.

The carrier entering Pearl Harbor towards the end of the film was in fact the Iwo Jima-class amphibious assault ship USS Tripoli (LPH-10), returning to port. The "Japanese" aircraft carrier was the anti-submarine carrier USS Yorktown (CVS-10). The Japanese A6M Zero fighters, and somewhat longer "Kate" torpedo bombers or "Val" dive bombers were heavily modified RCAF Harvard (T-6 Texan) and BT-13 Valiant pilot training aircraft. The large fleet of Japanese aircraft was created by Lynn Garrison, a well-known aerial action coordinator, who produced a number of conversions. Garrison and Jack Canary coordinated the actual engineering work at facilities in the Los Angeles area. These aircraft still make appearances at air shows.[15]

A Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress’s actual crash landing during filming, a result of a jammed landing gear, was filmed and used in the final cut. A total of five Boeing B-17s were obtained for filming. Other U.S. aircraft used are the Consolidated PBY Catalina and, especially, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk (two flyable examples were used). Predominately, P-40 fighters are used to depict the U.S. defenders with a full-scale P-40 used as a template for fiberglass replicas (some with working engines and props) that were strafed and blown up during filming.[16] Fleischer also said a scene involving a P-40 model crashing into the middle of a line of P-40s was unintended, as it was supposed to crash at the end of the line. The stuntmen involved in the scene were actually running for their lives.[17]

Historical accuracy [edit]

Parts of the film showing the takeoff of the Japanese aircraft utilize an Essex-class aircraft carrier, USS Yorktown (CVS-10), which was commissioned in 1943 and modernized after the war to have an angled flightdeck. [18] The ship was leased by the film producers, who needed an aircraft carrier for the film; Yorktown was scheduled to be decommissioned shortly afterwards. It was used largely in the takeoff sequence of the Japanese attack aircraft. The sequence shows interchanging shots of models of the Japanese aircraft carriers and the Yorktown. It does not look like any of the Japanese carriers involved in the attack, due to its large bridge island and its angled landing deck. The Japanese carriers had small bridge islands, and angled flight decks were not invented until after the war. [19]In addition, during the scene in which Admiral Halsey is watching bombing practice an aircraft carrier with the hull number 14 is shown. Admiral Halsey was on the USS Enterprise (CV-6), not the Essex-class carrier USS Ticonderoga (CV-14), which would not be commissioned until 1944. This is understandable, however, as both the Enterpise and all six of the Japanese carriers from the attack had been scrapped and sunk, respectively. Enterprise was scrapped in 1959, and four of the six, including Akagi, were sunk not six months after the attack at the Battle of Midway.

In Tora! Tora! Tora!, an error involves the model of the Japanese carrier Akagi. In the film, Akagi's bridge island is positioned on the starboard side of the ship, which is typical on most aircraft carriers. However, the aircraft carrier Akagi was an exception; its bridge island was on the port side of the ship. Despite this, the bridge section appeared accurately as a mirrored version of Akagi's real port-side bridge.[20] Secondly, all the Japanese aircraft in the footage bear the markings of Akagi's aircraft (a single vertical red stripe following the red sun symbol of Japan), even though five other aircraft carriers participated, each having its own markings. In addition, the markings do not display the aircrafts' identification numbers as was the case in the actual battle. The white surround on the roundel on the Japanese aircraft was only used from 1942 onwards. Prior to this the roundel was red only.[21]

The USS Ward (DD-139) was an old "4-piper" destroyer commissioned in 1918; the ship used in the movie, USS Savage (DE-386), which portrays the Ward looked far different from the original destroyer.[22] In addition, in the movie she fired two shots from her #1 turret. In reality, the Ward fired the first shot from the #1 4" un-turreted gunmount and the second shot from the #3 wing mount.[23]

A stern section of the USS Nevada (BB-36) was built that was also used to portray the USS Arizona and other U.S. battleships. The lattice mast (or cage mast) section of the California-class/Maryland-class battleship was built beside the set of the USS Nevada stern section, but not built upon a set of a deck, but on the ground as the footage in the movie only showed the cage mast tower. The large scale model of the stern shows the two aft gun turrets with three gun barrels in each; in reality, Nevada had two heightened fore and aft turrets with two barrels each while the lower two turrets fore and aft had three barrels each. Another model of Nevada, used in the film to portray the whole ship, displays the turrets accurately. It should be noted that the reason for this anomaly is because the aft section model was used in the film to portray both USS Nevada and USS Arizona (BB-39). The ships looked remarkably similar except that Arizona had four triple turrets and a slightly different stern section. Footage and photographs not used in the film show the cage mast as being built on the ground. The USS Nevada/USS Arizona stern section was shown exploding to represent the explosion that destroyed the Arizona.

The film has a Japanese Zero fighter being damaged over a Naval base and then deliberately crashing into a Naval Base hangar. This is actually a composite of three incidents at Pearl Harbor attack: in the first wave a Japanese Zero crashed into Fort Kamehameha's ordnance building; in the second wave, a Japanese Zero did deliberately crash into a hillside after U.S. Navy CPO John William Finn at Naval Air Station at Kāne'ohe Bay had shot and damaged the aircraft; also during the second wave, a Japanese aircraft that was damaged crashed into the seaplane tender USS Curtiss.[24]

During a number of shots of the attack squadrons traversing across Oahu, a small cross can be seen on one of the mountainsides. The cross was actually erected after the attack as a memorial to the victims of the attack.[25]

Reception [edit]

At the time of its initial movie release, Tora! Tora! Tora! was thought to be a box office flop in North America,[26] although its domestic box office of $29,548,291 led to its being ranked the ninth highest-grossing film of 1970.[27] It was a major hit in Japan and over the years, home media releases provided a larger overall profit.[28][29]

Roger Ebert felt that Tora! Tora! Tora! was one of the deadest, dullest blockbusters ever made" and suffered from not having "some characters to identify with." In addition, he criticized the film for poor acting and special effects in his 1970 review.[30]Vincent Canby, reviewer for The New York Times, was similarly unimpressed, noting the film was "nothing less than a $25-million irrelevancy."[31] Variety also found the film to be boring; however, the magazine praised the film's action sequences and production values.[32] James Berardinelli, however, said it was "rare for a feature film to attain the trifecta of entertaining, informing, and educating."[33] Charles Champlin in his review for the Los Angeles Times on September 23, 1970, considered the movie's chief virtues as a "spectacular", and the careful recreation of a historical event.[34]

Despite the initial negative reviews, the film was critically acclaimed for its vivid action scenes, and found favor with aviation and history aficionados.[35] However, even the team of Jack Hardwick and Ed Schnepf who have been involved in research on aviation films, had relegated Tora! Tora! Tora! to the "also-ran" status, due to its slow-moving plotline.[35]The film holds a 65% "Fresh" rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes,[36] based on 17 critical reviews.

Several later films and TV series relating to World War II in the Pacific have used footage from Tora! Tora! Tora! due to the film's "almost perfect documentary accuracy". These productions include the films Midway (1976; in the Tora! Tora! Tora! DVD commentary, Fleischer is angry that Universal used the footage), Pearl (TV mini-series 1978), From Here to Eternity (TV mini-series 1979), The Final Countdown (1980), and Australia (2008) as well as the Magnum, P. I. television series episode titled "Lest We Forget" (first airdate February 12, 1981).[37]

Honors [edit]

Tora! Tora! Tora! won an Academy Award for best special effects.[34] The film was also nominated in a further four categories: Best Art Direction (Jack Martin Smith, Yoshirō Muraki, Richard Day, Taizô Kawashima, Walter M. Scott, Norman Rockett, Carl Biddiscombe), Best Cinematography, Best Editing and Best Sound (Murray Spivack, Herman Lewis).[38]

Popular culture [edit]

The name of the film has been borrowed – and parodied – for various media productions, including the "Torah Torah Torah" episodes of the television shows Magnum, P.I. and NYPD Blue, the band Tora! Tora! Torrance!, the Depeche Mode song "Tora! Tora! Tora!" from their first album Speak & Spell, and the Tory! Tory! Tory! documentary on Thatcherism.

'TV영화관' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Broken Trail (0) | 2013.06.02 |

|---|---|

| Con Air (0) | 2013.06.02 |

| Air Force (film) (0) | 2013.05.29 |

| Battle of the Bulge (film) (0) | 2013.05.28 |

| Friendly Persuasion (0) | 2013.05.26 |