New Orleans

| New Orleans Ville de La Nouvelle-Orléans Orleans Parish | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| — City and Parish — | |||

| City of New Orleans | |||

| From top left: A typical New Orleans mansion off St. Charles Avenue, a streetcar passing by Loyola University and Tulane University, the skyline of the Central Business District, Jackson Square, and a view of Royal Street in the French Quarter. | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): The Crescent City; The Big Easy; The City That Care Forgot; Nawlins; NOLA | |||

| Location in the State of Louisiana | |||

|

| |||

| Coordinates: 29°57′53″N 90°4′14″W / 29.96472°N 90.07056°W | |||

| Country | |||

| State | |||

| Parish | |||

| Founded | 1718 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Mitch Landrieu (D) | ||

| Area | |||

| • City and Parish | 350.2 sq mi (907 km2) | ||

| • Land | 180.6 sq mi (467.6 km2) | ||

| • Water | 169.7 sq mi (439.4 km2) | ||

| • Metro | 3,755.2 sq mi (9,726.6 km2) | ||

| Elevation | -6.5 to 20 ft (-2 to 6 m) | ||

| Population (2011)[1] | |||

| • City and Parish | 360,740 | ||

| • Density | 1,965/sq mi (759/km2) | ||

| • Metro | 1,167,764 | ||

| Demonym | New Orleanian | ||

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) | ||

| Area code(s) | 504 | ||

| Website | nola.gov | ||

| Wikivoyage has travel information related to: New Orleans |

New Orleans (pron.: /nuː ˈɔrliənz/ or /ˈnuː ɔrˈliːnz/, locally /nuː ˈɔrlənz/ or /ˈnɔrlənz/; French: La Nouvelle-Orléans [la nuvɛlɔʁleɑ̃] (![]() listen)) is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The population of the city was 343,829 as of the 2010 U.S. Census.[2] The New Orleans metropolitan area (New Orleans–Metairie–Kenner Metropolitan Statistical Area) had a population of 1,167,764 in 2010 and was the 46th largest in the United States.[3] The New Orleans–Metairie–Bogalusa Combined Statistical Area, a larger trading area, had a 2010 population of 1,214,932.[4]

listen)) is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The population of the city was 343,829 as of the 2010 U.S. Census.[2] The New Orleans metropolitan area (New Orleans–Metairie–Kenner Metropolitan Statistical Area) had a population of 1,167,764 in 2010 and was the 46th largest in the United States.[3] The New Orleans–Metairie–Bogalusa Combined Statistical Area, a larger trading area, had a 2010 population of 1,214,932.[4]

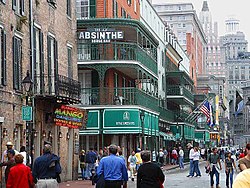

The city is named after Orléans, a city located on the Loire River in Centre, France, and is well known for its distinct French Creole architecture, as well as its cross-cultural and multilingual heritage.[5] New Orleans is also famous for its cuisine, music (particularly as the birthplace of jazz),[6][7] and its annual celebrations and festivals, most notably Mardi Gras. The city is often referred to as the "most unique"[8] in America.[9][10][11][12][13]

New Orleans is located in southeastern Louisiana, straddling the Mississippi River. The city and Orleans Parish (French: paroisse d'Orléans) are coterminous.[14] The city and parish are bounded by the parishes of St. Tammany to the north, St. Bernard to the east, Plaquemines to the south and Jefferson to the south and west.[14][15][16] Lake Pontchartrain, part of which is included in the city limits, lies to the north and Lake Borgne lies to the east.[16]

History

Beginnings through the 19th century

La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans) was founded May 7, 1718, by the French Mississippi Company, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, on land inhabited by the Chitimacha. It was named for Philippe d'Orléans, Duke of Orléans, who was Regent of France at the time. His title came from the French city of Orléans. The French colony was ceded to the Spanish Empire in the Treaty of Paris (1763). During the American Revolutionary War, New Orleans was an important port to smuggle aid to the rebels, transporting military equipment and supplies up the Mississippi River. Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez successfully launched the southern campaign against the British from the city in 1779.[17] New Orleans remained under Spanish control until 1801, when it reverted to French control. Nearly all of the surviving 18th century architecture of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) dates from this Spanish period. (The most notable exception being the Old Ursuline Convent.)[18] Napoleon sold the territory to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Thereafter, the city grew rapidly with influxes of Americans, French, Creoles, Irish, Germans and Africans. Major commodity crops of sugar and cotton were cultivated with slave labor on large plantations outside the city.

The Haitian Revolution ended in 1804 and established the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first led by blacks. It had occurred over several years in what was then the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Thousands of refugees from the revolution, both whites and free people of color (affranchis or gens de couleur libres), arrived in New Orleans, often bringing African slaves with them. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out more free black men, the French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. As more refugees were allowed in Louisiana, Haitian émigrés who had first gone to Cuba also arrived.[19] Many of the white francophones had been deported by officials in Cuba in response to Bonapartist schemes in Spain.[20]

Nearly 90 percent of the new immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites; 3,102 free persons of African descent; and 3,226 enslaved persons of African descent, doubling the city's French-speaking population. The city became 63 percent black in population, a greater proportion than Charleston, South Carolina's 53 percent.[19]

During the last campaign of the War of 1812, the British sent a force of 11,000 soldiers in an attempt to capture New Orleans. Despite great challenges, the young Andrew Jackson successfully cobbled together a motley crew of local militia, free blacks, US Army regulars, Kentucky riflemen, and local privateers to decisively defeat the British troops, led by Sir Edward Pakenham, in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. The armies were unaware that the Treaty of Ghent had already ended the war on December 24, 1814.

As a principal port, New Orleans played a major role during the antebellum era in the Atlantic slave trade. Its port also handled huge quantities of commodities for export from the interior and imported goods from other countries, which were warehoused and then transferred in New Orleans to smaller vessels and distributed the length and breadth of the vast Mississippi River watershed. The river in front of the city was filled with steamboats, flatboats, and sailing ships. Despite its dealings with the slave trade, New Orleans at the same time had the largest and most prosperous community of free persons of color in the nation, who were often educated and middle-class property owners.[6][21]

Dwarfing in population the other cities in the antebellum South, New Orleans had the largest slave market in the domestic slave trade, which expanded after the United States' ending of the international trade in 1808. Two-thirds of the more than one million slaves brought to the Deep South arrived via the forced migration of the domestic slave trade. The money generated by sales of slaves in the Upper South has been estimated at fifteen percent of the value of the staple crop economy. The slaves represented half a billion dollars in property, and an ancillary economy grew up around the trade in slaves—for transportation, housing and clothing, fees, etc., estimated at 13.5 percent of the price per person. All of this amounted to tens of billions of dollars (2005 dollars, adjusted for inflation) during the antebellum period, with New Orleans as a prime beneficiary.[22]

According to the historian Paul Lachance, "the addition of white immigrants to the white creole population enabled French-speakers to remain a majority of the white population until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of free persons of color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820."[23] Large numbers of German and Irish immigrants began arriving at this time. The population of the city doubled in the 1830s and by 1840, New Orleans had become the wealthiest and the third-most populous city in the nation.[24] In the 1850s, white Francophones remained an intact and vibrant community; they maintained instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts.[25]

As the Creole elite feared, during the war, their world changed. In 1862, the Union general Ben Butler abolished French instruction in schools, and statewide measures in 1864 and 1868 further cemented the policy.[26] By the end of the 19th century, French usage in the city had faded significantly.[27] However, as late as 1902 one-fourth of the population of the city spoke French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths was able to understand the language perfectly,"[28] and as late as 1945, one still encountered elderly Creole women who spoke no English.[29] The last major French language newspaper in New Orleans, L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans, ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years;[30] according to some sources Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.[31]

During the American Civil War, the Union captured New Orleans early; the city was spared the destruction suffered by many other cities of the American South.[32]

During Reconstruction, New Orleans was within the Fifth Military District of the United States. Louisiana was readmitted to the Union in 1868, and its Constitution of 1868 granted universal manhood suffrage. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, then-lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth as governor of Louisiana, becoming the first non-white governor of a U.S. state, and the last African American to lead a U.S. state until Douglas Wilder's election in Virginia, 117 years later. In New Orleans, Reconstruction was marked by the Mechanics Institute race riot (1866). The city operated successfully a racially integrated public school system. Damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade for the port city for some time, as the government tried to restore infrastructure. The nationwide Panic of 1873 also slowed economic recovery.

Reconstruction ended in Louisiana in 1877. Since 1874, the White League, an insurgent paramilitary group that supported the Democratic Party, had succeeded in disrupting and suppressing the black vote in several elections and running off Republican officeholders. With their help, the white Democrats, the so-called Redeemers, regained control of the state legislature. They imposed Jim Crow laws, imposing racial segregation and, with the new constitution and election laws at the end of the century, disfranchising freedmen. Unable to vote, African Americans could not serve on juries or in local office, and were closed out of politics for several generations in the state. Public schools were racially segregated and remained so until 1960.

New Orleans' large community of well-educated, often French-speaking free persons of color (gens de couleur libres), who had not been enslaved prior to the Civil War, sought to fight back against Jim Crow. As part of their campaign, they recruited one of their own, Homer Plessy, to test whether Louisiana's newly enacted Separate Car Act was constitutional. Plessy boarded a commuter train departing New Orleans for Covington, Louisiana, sat in the car reserved for whites only, and was arrested. The case resulting from this incident, Plessy v. Ferguson, was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896. The court, in finding that "separate but equal" accommodations were constitutional, effectively upheld Jim Crow measures. In practice, African American public schools and accommodations were generally underfunded. The ruling contributed to this period as the nadir of race relations reached during this period.

20th century

New Orleans reached its most consequential position as an economic and population center in relation to other American cities in the decades prior to 1860; as late as that year, it was the nation's fifth-largest city and by far the largest in the American South.[33] Though New Orleans continued to grow in size, from the mid-19th century onward, first the emerging industrial and railroad hubs of the Midwest overtook the city in population, then the rapidly growing metropolises of the Pacific Coast in the decades before and after the turn of the 20th century, then other Sun Belt cities in the South and West in the post–World War II period surpassed New Orleans in population. Construction of railways and highways decreased river traffic, diverting goods to other transportation corridors and markets.[33] From the late 1800s, most 10-year censuses depicted New Orleans sliding down the list of largest American cities. Reminded every ten years of its declining relative importance, New Orleans would periodically mount attempts to regain its economic vigor and pre-eminence, with varying degrees of success. In 1950, the Census Bureau reported New Orleans' population as 68% white and 31.9% black.[34]

By the mid-20th century, New Orleanians saw that their city was being surpassed as the leading urban area in the South. By 1950, Houston, Dallas and Atlanta exceeded New Orleans in size, and in 1960 Miami eclipsed New Orleans, even as the latter's population reached what would be its historic peak that year.[33] Like most older American cities in the postwar period, highway construction and suburban development drew residents from the center city, though the New Orleans metropolitan area continued expanding in population – just never as rapidly as other major cities in the Sun Belt. While the port remained one of the largest in the nation, automation and containerization resulted in significant job losses. The city's relative fall in stature meant that its former role as banker to the South was inexorably supplanted by competing companies in larger peer cities. New Orleans' economy had always been more based on trade and financial services than on manufacturing, but the city's relatively small manufacturing sector also shrank in the post–World War II period. Despite some economic development successes under the administrations of DeLesseps "Chep" Morrison (1946–1961) and Vic Schiro (1961–1970), metropolitan New Orleans' growth rate consistently lagged behind more vigorous cities.

During the later years of Morrison's administration, and for the entirety of Schiro's, the city was at the center of the Civil Rights struggle. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was founded in the city, lunch counter sit-ins were held in Canal Street stores, and a very prominent and violent series of confrontations occurred when the city attempted school desegregation, in 1960. That episode witnessed the first occasion of a black child attending an all-white elementary school in the South, when six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrated William Frantz Elementary School in the city's Ninth Ward. The Civil Rights Movement's success in gaining federal passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 provided enforcement of constitutional rights, including voting for blacks. Together, these resulted in the most far-reaching changes in in New Orleans' 20th century history.[35] Though legal and civil equality were re-established by the end of the 1960s, a large gap in income levels and educational attainment persisted between the city's White and African-American communities.[36] As the middle class and wealthier members of both races left the center city, its population's income level dropped and it became proportionately more African American. From 1980, the African-American majority has elected officials from its own community. They have struggled to narrow the gap by creating conditions conducive to the economic uplift of the African-American community.

New Orleans became increasingly dependent on tourism as an economic mainstay, by the administrations of Sidney Barthelemy (1986–1994) and Marc Morial (1994–2002). Relatively low levels of educational attainment, high rates of household poverty and rising crime threatened the prosperity of the city in the later decades of the century.[36] The negative effects of these socioeconomic conditions contrasted with the changes to the economy of the United States, which were based on a post-industrial, knowledge-based paradigm where brains were far more important to advancement than brawn.

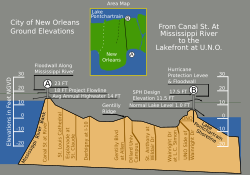

New Orleans' government and business leaders believed they needed to drain outlying areas to provide for the city's expansion. The most ambitious development during this period was a drainage plan devised by engineer and inventor A. Baldwin Wood and designed to break the surrounding swamp's stranglehold on the city's geographic expansion. Until then, urban development in New Orleans was largely limited to higher ground along the natural river levees and bayous. Wood's pump system allowed the city to drain huge tracts of swamp and marshland and expand into low-lying areas. Over the 20th century, rapid subsidence, both natural and human-induced, left these newly populated areas several feet below sea level.[37][38]

New Orleans was vulnerable to flooding even before the city's footprint departed from the natural high ground near the Mississippi River. In the late 20th century, however, scientists and New Orleans residents gradually became aware of the city's increased vulnerability. In 1965, Hurricane Betsy killed dozens of residents, although the majority of the city remained dry. The rain-induced flood of May 8, 1995 demonstrated the weakness of the pumping system. After that event, measures were undertaken to dramatically upgrade pumping capacity. By the 1980s and 1990s, scientists observed that extensive, rapid and ongoing erosion of the marshlands and swamp surrounding New Orleans, especially that related to the Mississippi River – Gulf Outlet Canal, had left the city more exposed to hurricane-induced catastrophic storm surges than it before in its history.

21st century

Hurricane Katrina

New Orleans was catastrophically affected by what the University of California Berkeley's Dr. Raymond B. Seed called "the worst engineering disaster in the world since Chernobyl," when the Federal levee system failed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[39] By the time the hurricane approached the city at the end of August 2005, most residents had evacuated. As the hurricane passed through the Gulf Coast region, the city's federal flood protection system failed, resulting in the worst civil engineering disaster in American history.[40] Floodwalls and levees constructed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers failed below design specifications and 80% of the city flooded. Tens of thousands of residents who had remained in the city were rescued or otherwise made their way to shelters of last resort at the Louisiana Superdome or the New Orleans Morial Convention Center. More than 1,500 people were recorded as died in Louisiana, and others are still unaccounted for.[41] Before Hurricane Katrina, the city called for the first mandatory evacuation in its history, to be followed by another mandatory evacuation three years later with Hurricane Gustav.

Hurricane Rita

The city was declared off-limits to residents while efforts to clean up after Hurricane Katrina began. The approach of Hurricane Rita in September 2005 caused repopulation efforts to be postponed,[42] and the Lower Ninth Ward was reflooded by Rita's storm surge.

Post-disaster recovery

The Census Bureau in July 2006 estimated the population of New Orleans to be 223,000; a subsequent study estimated that 32,000 additional residents had moved to the city as of March 2007, bringing the estimated population to 255,000, approximately 56% of the pre-Katrina population level. Another estimate, based on data on utility usage from July 2007, estimated the population to be approximately 274,000 or 60% of the pre-Katrina population. These estimates are somewhat smaller than a third estimate, based on mail delivery records, from the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center in June 2007, which indicated that the city had regained approximately two-thirds of its pre-Katrina population.[43] In 2008, the Census Bureau revised upward its population estimate for the city, to 336,644.[44] Most recently, 2010 estimates show that neighborhoods that did not flood are near 100% of their pre-Katrina populations, and in some cases, exceed 100% of their pre-Katrina populations.[45]

Several major tourist events and other forms of revenue for the city have returned. Large conventions are being held again, such as those held by the American Library Association and American College of Cardiology.[46][47] College football events such as the Bayou Classic, New Orleans Bowl, and Sugar Bowl returned for the 2006–2007 season. The New Orleans Saints returned that season as well, following speculation of a move. The New Orleans Hornets returned to the city fully for the 2007–2008 season, having partially spent the 2006–2007 season in Oklahoma City. New Orleans successfully hosted the 2008 NBA All-Star Game and the 2008 BCS National Championship Game. The city hosted the first and second rounds of the 2007 NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament. New Orleans and Tulane University will be hosting the Final Four Championship in 2012. Additionally, the city will host Super Bowl XLVII on February 3, 2013 at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome.

Major annual events such as Mardi Gras and the Jazz & Heritage Festival were never displaced or cancelled. Also, an entirely new annual festival, "The Running of the Bulls New Orleans", was created in 2007.[48]

Geography

New Orleans is located at

29°57′53″N 90°4′14″W / 29.96472°N 90.07056°W (29.964722, −90.070556)[49] on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 miles (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 350.2 square miles (907 km2), of which 180.56 square miles (467.6 km2), or 51.55%, is land.[50]

The city is located in the Mississippi River Delta on the east and west banks of the Mississippi River and south of Lake Pontchartrain. The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

New Orleans was originally settled on the natural levees or high ground, along the Mississippi River. After the Flood Control Act of 1965, the United States Army Corps of Engineers built floodwalls and man-made levees around a much larger geographic footprint that included previous marshland and swamp. Whether or not this human interference has caused subsidence is a topic of debate. A study by an associate professor at Tulane University claims:

| “ | While erosion and wetland loss are huge problems along Louisiana's coast, the basement 30 to 50 feet (15 m) beneath much of the Mississippi Delta has been highly stable for the past 8,000 years with negligible subsidence rates.[51] | ” |

On the other hand, a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers claims that "New Orleans is subsiding (sinking)":[52]

| “ | Large portions of Orleans, St. Bernard, and Jefferson parishes are currently below sea level—and continue to sink. New Orleans is built on thousands of feet of soft sand, silt, and clay. Subsidence, or settling of the ground surface, occurs naturally due to the consolidation and oxidation of organic soils (called "marsh" in New Orleans) and local groundwater pumping. In the past, flooding and deposition of sediments from the Mississippi River counterbalanced the natural subsidence, leaving southeast Louisiana at or above sea level. However, due to major flood control structures being built upstream on the Mississippi River and levees being built around New Orleans, fresh layers of sediment are not replenishing the ground lost by subsidence.[52] | ” |

A recent study by Tulane and Xavier University notes that 51% of New Orleans is at or above sea level, with the more densely populated areas generally on higher ground. The average elevation of the city is currently between one and two feet (0.5 m) below sea level, with some portions of the city as high as 20 feet (6 m) at the base of the river levee in Uptown and others as low as 7 feet (2 m) below sea level in the farthest reaches of Eastern New Orleans.[53]

In 2005, storm surge from Hurricane Katrina caused catastrophic failure of the federally designed and built levees, flooding 80% of the city.[54][55] A report by the American Society of Civil Engineers says that "had the levees and floodwalls not failed and had the pump stations operated, nearly two-thirds of the deaths would not have occurred".[52]

New Orleans has always had to consider the risk of hurricanes, but the risks are dramatically greater today due to coastal erosion from human interference.[56] Since the beginning of the 20th century, it has been estimated that Louisiana has lost 2,000 square miles (5,000 km2) of coast (including many of its barrier islands), which once protected New Orleans against storm surge. Following Hurricane Katrina, the United States Army Corps of Engineers has instituted massive levee repair and hurricane protection measures to protect the city.

In 2006, Louisiana voters overwhelmingly adopted an amendment to the state's constitution to dedicate all revenues from off-shore drilling to restore Louisiana's eroding coast line.[57] Congress has allocated $7 billion to bolster New Orleans' flood protection.[58]

According to a study by the National Academy of Engineering and the National Research Council, Levees and floodwalls surrounding New Orleans—no matter how large or sturdy—cannot provide absolute protection against overtopping or failure in extreme events. Levees and floodwalls should be viewed as a way to reduce risks from hurricanes and storm surges, not as measures that completely eliminate risk. For structures in hazardous areas and residents who do not relocate, the committee recommended major floodproofing measures—such as elevating the first floor of buildings to at least the 100-year flood level.[59]

Cityscape

The Central Business District of New Orleans is located immediately north and west of the Mississippi River, and was historically called the "American Quarter" or "American Sector", and it includes Lafayette Square. Most streets in this area fan out from a central point in the city. Major streets of the area include Canal Street, Poydras Street, Tulane Avenue and Loyola Avenue. Canal Street functions as the street which divides the traditional "downtown" area from the "uptown" area.

Every street crossing Canal Street between the Mississippi River and Rampart Street, which is the northern edge of the French Quarter, has a different name for the "uptown" and "downtown" portions. For example, St. Charles Avenue, known for its street car line, is called Royal Street below Canal Street, though where it traverses the Central Business District between Canal and Lee Circle, it is properly called St. Charles Street.[70] Elsewhere in the city, Canal Street serves as the dividing point between the "South" and "North" portions of various streets. In the local parlance downtown means "downriver from Canal Street", while uptown means "upriver from Canal Street". Downtown neighborhoods include the French Quarter, Tremé, the 7th Ward, Faubourg Marigny, Bywater (the Upper Ninth Ward), and the Lower Ninth Ward. Uptown neighborhoods include the Warehouse District, the Lower Garden District, the Garden District, the Irish Channel, the University District, Carrollton, Gert Town, Fontainebleau, and Broadmoor. However, the Warehouse and the Central Business District, despite being above Canal Street, are frequently called "Downtown" as a specific region, as in the Downtown Development District.

Other major districts within the city include Bayou St. John, Mid-City, Gentilly, Lakeview, Lakefront, New Orleans East, and Algiers.

Architecture

New Orleans is world-famous for its abundance of unique architectural styles which reflect the city's historical roots and multicultural heritage. Though New Orleans possesses numerous structures of national architectural significance, it is equally, if not more, revered for its enormous, largely intact (even post-Katrina) historic built environment. Twenty National Register Historic Districts have been established, and fourteen local historic districts aid in the preservation of this tout ensemble. Thirteen of the local historic districts are administered by the New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission (HDLC), while one—the French Quarter—is administered by the Vieux Carre Commission (VCC). Additionally, both the National Park Service, via the National Register of Historic Places, and the HDLC have landmarked individual buildings, many of which lie outside the boundaries of existing historic districts.[71]

Many styles of housing exist in the city, including the shotgun house (originating from New Orleans) and the bungalow style. Creole townhouses, notable for their large courtyards and intricate iron balconies, line the streets of the French Quarter. Throughout the city, there are many other historic housing styles: Creole cottages, American townhouses, double-gallery houses, and Raised Center-Hall Cottages. St. Charles Avenue is famed for its large antebellum homes. Its mansions are in various styles, such as Greek Revival, American Colonial and the Victorian styles of Queen Anne and Italianate architecture. New Orleans is also noted for its large, European-style Catholic cemeteries, which can be found throughout the city.

For much of its history, New Orleans' skyline consisted of only low- and mid-rise structures. The soft soils of New Orleans are susceptible to subsidence, and there was doubt about the feasibility of constructing large high rises in such an environment. The 1960s brought the World Trade Center New Orleans and Plaza Tower, which demonstrated that high rises could stand firm on New Orleans' soil. One Shell Square took its place as the city's tallest building in 1972. The oil boom of the early 1980s redefined New Orleans' skyline again with the development of the Poydras Street corridor. Today, New Orleans' high rises are clustered along Canal Street and Poydras Street in the Central Business District.

'Louisiana' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 슈리브포트 (0) | 2019.06.19 |

|---|---|

| Shreveport, Louisiana (0) | 2019.06.19 |

| 허리케인 카트리나 (0) | 2018.11.06 |

| French Quarter (2) | 2013.02.02 |

| Superdome (0) | 2013.02.02 |