Oliver Hardy

Oliver Hardy | |

|---|---|

Hardy c. 1930 | |

| Born | Norvell Hardy January 18, 1892 Harlem, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | August 7, 1957 (aged 65) North Hollywood, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1914–1955 |

| Spouse(s) | Madelyn Saloshin (m. 1913–1921; divorced) Myrtle Reeves (m. 1921–1937; divorced) Virginia Lucille Jones (m. 1940) |

| Signature | |

Oliver Norvell Hardy (born Norvell Hardy, January 18, 1892 – August 7, 1957) was an American comic actor and one half of Laurel and Hardy, the double act that began in the era of silent films and lasted from 1927 to 1951. He appeared with Stan Laurel in 107 short films, feature films, and cameo roles.[1] He was credited with his first film Outwitting Dad in 1914. In some of his early works, he was billed as "Babe Hardy".

Contents

Early life and education[edit]

Oliver Hardy was born Norvell Hardy in Harlem, Georgia.[2] His father Oliver was a Confederate veteran who had been wounded at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862 and was a recruiting officer for Company K, 16th Georgia Regiment. The elder Oliver Hardy assisted his father in running the vestiges of the family cotton plantation following the Civil War. He then bought a share in a retail business and was elected full-time Tax Collector for Columbia County, Georgia. Hardy's mother Emily Norvell was the daughter of Thomas Benjamin Norvell and Mary Freeman, descended from Captain Hugh Norvell of Williamsburg, Virginia who arrived in Virginia before 1635. The elder Hardy and Norvell married March 12, 1890; it was her second marriage and his third.

The family moved to Madison, Georgia in 1891 before Norvell's birth.[3] He was likely born in Harlem, though some sources say that his birth occurred in Covington, Georgia, his mother's hometown. His father died less than a year after his birth. Hardy was the youngest of five children. His older brother Sam drowned in the Oconee River; Hardy pulled him from the river but was unable to resuscitate him.[4]

As a child, Hardy was sometimes difficult. He was sent to Georgia Military College in Milledgeville as a youngster. He was sent to Young Harris College in north Georgia in the 1905 fall semester when he was 13. He had little interest in formal education, although he acquired an early interest in music and theater. He joined a theatrical group and later ran away from a boarding school near Atlanta to sing with the group. His mother recognized his talent for singing and sent him to Atlanta to study music and voice with singing teacher Adolf Dahm-Petersen. He skipped some of his lessons to sing in the Alcazar Theater for $3.50 a week.

Hardy began styling himself "Oliver Norvell Hardy", adding the first name "Oliver" as a tribute to his father. He appeared as "Oliver N. Hardy" in the 1910 U.S. census,[N 1] and he used "Oliver" as his first name in all subsequent legal records, marriage announcements, etc. Hardy was initiated into Freemasonry at Solomon Lodge No. 20 in Jacksonville, Florida. He was inducted into the Grand Order of Water Rats along with Stan Laurel.[5]

Career[edit]

Early career[edit]

In 1910, a movie theater opened in Hardy's hometown of Milledgeville, and he became the projectionist, ticket taker, janitor, and manager. He soon became obsessed with the new motion picture industry and was convinced that he could do a better job than the actors that he saw. A friend suggested that he move to Jacksonville, Florida, where some films were being made, which he did in 1913. He worked in Jacksonville as a cabaret and vaudeville singer at night, and at the Lubin Manufacturing Company during the day. It was at this time that he met Madelyn Saloshin, a pianist whom he married on November 17, 1913 in Macon, Georgia.

The next year, he made his first movie Outwitting Dad (1914) for the Lubin studio, billed as O. N. Hardy. In his personal life, he was known as "Babe" Hardy, and he was billed as "Babe Hardy" in many of his later films at Lubin. He was a big man, standing 6-foot 1-inch and weighing up to 300 pounds, and his size placed limitations on the roles that he could play. He was most often cast as the villain, but he also had roles in comedy shorts, his size complementing the character. By 1915, Hardy had made 50 short one-reel films at Lubin. He moved to New York and made films for the Pathé, Casino, and Edison Studios, he returned to Jacksonville where he made films for the Vim Comedy Company. That studio closed after Hardy discovered that the owners were stealing from the payroll.[6] He then worked for the King Bee studio, which bought Vim, and worked with Billy Ruge, Billy West (a Charlie Chaplin imitator), and comedic actress Ethel Burton Palmer. He continued playing the villains for West well into the early 1920s, often imitating Eric Campbell to West's Chaplin.

In 1917, Hardy moved to Los Angeles, working freelance for several Hollywood studios, and he made more than 40 films for Vitagraph between 1918 and 1923, mostly playing the "heavy" for Larry Semon. In 1919, he separated from his wife, ending with a provisional divorce in November 1920 which was finalized on November 17, 1921. on November 24, 1921, he married actress Myrtle Reeves. This marriage was also unhappy, and Reeves was said to have become an alcoholic.[7][8]

In 1921, he appeared in the movie The Lucky Dog produced by Broncho Billy Anderson and starring Stan Laurel.[9] Hardy played the part of a robber trying to hold up Stan's character. They did not work together again for several years. In 1924, Hardy began working at Hal Roach Studios with the Our Gang films and Charley Chase. In 1925, he starred as the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz. Also that year he was in the film Yes, Yes, Nanette!, starring Jimmy Finlayson and directed by Stan Laurel. (In later, years Finlayson frequently was a supporting actor in the Laurel and Hardy film series.)[10] He also continued playing supporting roles in films featuring Clyde Cooke and Bobby Ray.

In 1926, Hardy was scheduled to appear in Get 'Em Young, but he was unexpectedly hospitalized after being burned by a hot leg of lamb. Laurel had been working as a gag man and a director at Roach Studios, so he was recruited to fill in.[11] Laurel continued to act and appeared in 45 Minutes from Hollywood with Hardy, although they did not share any scenes together.

With Stan Laurel[edit]

In 1927, Laurel and Hardy began sharing screen time together in Slipping Wives, Duck Soup (no relation to the 1933 Marx Brothers' film), and With Love and Hisses. Roach Studios' supervising director Leo McCarey recognized the audience reaction to the two and began teaming them together, which led to the start of a Laurel and Hardy series later that year.

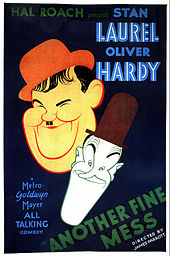

They began producing a huge body of short movies, including The Battle of the Century (1927) (with one of the largest pie fights ever filmed),[citation needed] Should Married Men Go Home? (1928), Two Tars (1928), Unaccustomed As We Are (1929, marking their transition to talking pictures) Berth Marks (1929), Blotto (1930), Brats (1930), Another Fine Mess (1930), Be Big! (1931), and many others. In 1929, they appeared in their first feature, in one of the revue sequences of Hollywood Revue of 1929, and the following year they appeared as the comic relief in a lavish Technicolor musical feature entitled The Rogue Song. This film marked their first appearance in color, yet only a few fragments of this film survive. In 1931, they starred in their first full-length movie Pardon Us, and they continued to make features and shorts until 1935. The 1932 film The Music Box won an Academy Award for best short film, their only effort to receive such an award.

In 1937, Hardy and Myrtle Reeves divorced. He made Zenobia with Harry Langdon in 1939 while waiting for a contractual issue to be resolved between Laurel and Hal Roach. Eventually, however, new contracts were agreed upon and the team was lent to producer Boris Morros at General Service Studios to make The Flying Deuces (1939). While on the lot, Hardy fell in love with Virginia Lucille Jones, a script girl whom he married the next year. They enjoyed a happy marriage until his death.

In 1939, Laurel and Hardy made A Chump at Oxford and Saps at Sea before leaving Roach Studios. They began performing for the USO, supporting the Allied troops during World War II. They teamed up to make films for 20th Century Fox and later Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. They made more money at the bigger studios, but they had very little artistic control; critics[who?] say that these films lack the very qualities which had made Laurel and Hardy worldwide names. Their last Fox feature was The Bullfighters (1945), after which they declined to extend their contract with the studio.

In 1947, Laurel and Hardy went on a six-week tour of the United Kingdom. They were initially unsure of how they would be received, but they were mobbed wherever they went. The tour was lengthened to include engagements in Scandinavia, Belgium, France, and a Royal Command Performance for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Biographer John McCabe writes[where?] that they continued to make live appearances in the United Kingdom and France until 1954, often using new sketches and material that Laurel had written for them.

In 1949, Hardy's friend John Wayne asked him to play a supporting role in The Fighting Kentuckian. Hardy had previously worked with Wayne and John Ford in a charity production of the play What Price Glory? while Laurel began treatment for his diabetes a few years previously. He was initially hesitant, but he accepted the role at Laurel's insistence. Frank Capra invited him to play a cameo role in Riding High with Bing Crosby in 1950.

During 1950–51, Laurel and Hardy made their final film Atoll K (also known as Utopia). It was a simple concept; Laurel inherits an island, and the boys set out to sea where they encounter a storm and discover a brand new island, rich in uranium, making them powerful and wealthy. However, the film was produced by a consortium of European interests, with an international cast and crew that could not speak to each other.[12] In addition, Laurel had to rewrite the script to make it fit the comedy team's style, and both suffered serious physical illness during the filming.

Laurel and Hardy made two live television appearances: in 1953 on a live broadcast of the BBC-TV show "Face the Music", and in December 1954 on NBC's This Is Your Life. They also appeared in a filmed insert for the BBC-TV show This Is Music Hall in 1955, their final appearance together. The pair contracted with Hal Roach, Jr. to produce a series of TV shows based on the Mother Goose fables in 1955. According to biographer John McCabe, they were to be filmed in color for NBC, but the series was postponed when Laurel suffered a stroke and required a lengthy convalescence. Later that year while Laurel was recovering, Hardy had a heart attack and stroke from which he never recovered.

Death[edit]

Hardy suffered a mild heart attack in May 1954, and he began looking after his health for the first time in his life. He lost more than 150 pounds in a few months, which completely changed his appearance. Letters written by Laurel refer to Hardy having terminal cancer,[13] and some[who?] have thought that this was the real reason for Hardy's rapid weight loss. Both men were heavy smokers; Hal Roach said that they were a couple of "freight train smoke stacks".[14]

Hardy suffered a major stroke on September 14, 1956 which left him confined to bed and unable to speak for several months. He remained at home in the care of his wife Lucille. He suffered two more strokes in early August 1957 and slipped into a coma, and he died from cerebral thrombosis on August 7, 1957 at age 65.[15][N 2] He was cremated and his ashes are interred in the Masonic Garden of Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood.[16] Laurel was too ill to attend the funeral,[17] but he said that "Babe would understand."[18]

Legacy[edit]

- Hardy's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is located at 1500 Vine Street, Hollywood, California

- Laurel and Hardy were inducted into the Grand Order of Water Rats[19]

- There is a small Laurel and Hardy Museum in Hardy's hometown of Harlem, Georgia which opened on July 15, 2000, and there is an annual Oliver Hardy Festival in this town

Filmography[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ He was recorded as "Oliver M. Hardy" (not "N"), an "electrician" at an "electric theater". He was mistakenly listed as the "son" of Roy J. Baisden in his census listing.

- ^ Quote: "Oliver Hardy, the fat, always frustrated partner of the famous movie comedy team of Laurel and Hardy, died early today at the North Hollywood home of his mother-in-law, Mrs. Monnie L. Jones. Mr. Hardy, who was 65 years old, suffered a paralytic stroke last Sept. 12."

Citations

- ^ Rawlngs, Nate. "Top 10 Across-the-Pond Duos", Time, 20 July 2010. Retrieved: 18 June 2012.

- ^ Vincent Canby, "Critics Notebook; Laurel With and Without Hardy", The New York Times, 1990. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Wilson III, Robert J. (2003). "Oliver Hardy in Georgia, 1903-1913". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 87 (3/4): 359–388. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "This is Your Life", Episode December 1, 1954.

- ^ "Roll of Honour".

- ^ "Creator: Bletcher, Billy, 1894-1979, Title, Dates: Billy Bletcher's Vim Southern Studio motion picture photographs, 1915-1917." Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine. State Archives of Florida online Catalog. Retrieved: October 12, 2010.

- ^ [1] "Sons of the Desert: Oliver Hardy Biography" Retrieved: July 11, 2017

- ^ [2] "Oliver Hardy" Retrieved: July 11, 2017

- ^ "The Lucky Dog (1921)." IMDb.com. Retrieved: March 20, 2010.

- ^ Louvish 2001, p. 182

- ^ Evanier, Mark. "POV: Popint of View- Laurel and Hardy." Archived 2009-05-12 at the Wayback Machine. povonline.com. Retrieved: March 20, 2010.

- ^ Aping, Norbert. The Final Film of Laurel and Hardy. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7864-3302-5.

- ^ "Rubber Stamp- 25406-1/2 Malibu Rd., Malibu, CA - Typewritten." Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine. Letters from Stan. Retrieved: July 24, 2011.

- ^ "The Stan Laurel Correspondence: 1957." Archived 2008-07-20 at the Wayback Machine. lettersfromstan.com. Retrieved: March 20, 2010.

- ^ "Oliver Hardy of Film Team Dies. Co-Star of 200 Slapstick Movies. Portly Master of the Withering Look and 'Slow Burn'. Features Popular on TV." The New York Times, August 8, 1957. Retrieved: March 20, 2010.

- ^ "Oliver Hardy." FreeMasonry.bcy.ca. Retrieved: March 20, 2010.

- ^ "Letters from Stan - August 1957" Retrieved: August 31, 2016

- ^ "Last Words - Epitaphs" Retrieved: July 11, 2017

- ^ "Roll of Honour".

Bibliography

- Louvish, Simon (2001). Stan and Ollie: The Roots of Comedy. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-21590-4.

- Marriot, A.J. Laurel & Hardy: The British Tours. Hitchen, Herts, UK: AJ Marriot, 1993. ISBN 0-9521308-0-7.

- McCabe, John. Babe: The Life of Oliver Hardy. London: Robson Books Ltd., 2004. ISBN 1-86105-781-4.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oliver Hardy. |

- Oliver Hardy on IMDb

- Oliver Hardy at the TCM Movie Database

- Oliver Hardy at Find a Grave

- Free viewing of Bouncing Baby (1916), made available for public use by the State Archives of Florida

- Oliver Hardy's obituaries in the Los Angeles Times and Los Angeles Mirror-News

- Oliver Hardy, Genius of Comedy historical marker in Madison, Georgia

- The Milledgeville Hotel and Oliver Hardy historical marker in Milledgeville, Georgia

- Oliver Norvell Hardy historical marker in Harlem, Georgia

- Laurel and Hardy

- 1892 births

- 1957 deaths

- 20th-century American comedians

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th Century Fox contract players

- Grand Order of Water Rats members

- American Freemasons

- American male comedians

- American male film actors

- American male silent film actors

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American stunt performers

- Burials at Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery

- Deaths from neurological disease

- Hal Roach Studios actors

- Male actors from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Male actors from Jacksonville, Florida

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players

- Norvell family

- People from Columbia County, Georgia

- Silent film comedians

- Vaudeville performers

- Young Harris College alumni

- American male comedy actors

'TV영화관' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 멋진 인생 (0) | 2018.12.15 |

|---|---|

| Laurel and Hardy (0) | 2018.12.12 |

| 올리버 하디 (0) | 2018.12.12 |

| 스탠 로럴 (0) | 2018.12.12 |

| Stan Laurel (0) | 2018.12.12 |